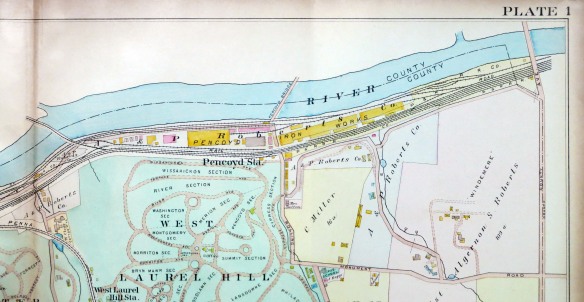

This is my unedited version of the story I wrote for Hidden City Philadelphia, which was published on January 11, 2017. The Pencoyd Iron Works was located on a strip of land adjoining the Schuylkill River across from the Manayunk neighborhood of Philadelphia, and closed at the end of 1943.

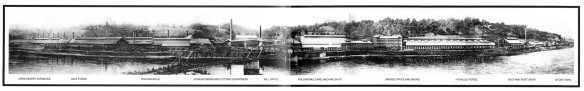

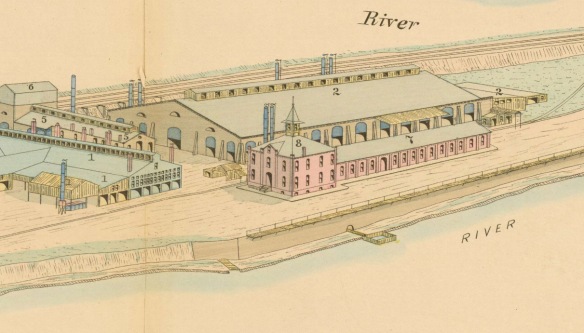

Panoramic View of the Pencoyd Iron Works c1900 | Credit: LMHS

Manayunk’s iconic concrete rail bridge enjoyed its first full season as a pedestrian crossing in 2016, as the Cynwyd Heritage Trail proves to be a popular cycling and strolling destination. Equally exciting, last year brought another, less known Schuylkill rail bridge back into use; visitors to Manayunk’s Main Street may have noticed the one lane newly-painted light green bridge crossing the river near the junction of Ridge Avenue. Encased in weeds and left forgotten for years, this 117 year old double-span Parker truss bridge was built by the namesake Pencoyd Iron works to connect their factory directly with customers across the river. The span is now granted public access as part of the new Pencoyd Trail.

The Pencoyd Bridge in 2017 | Credit: Mick Ricereto

The Pencoyd Bridge was restored by today’s owners of the riverfront in Lower Merion, Penn Real Estate, as part of the new Pencoyd Trail which traverses their property. This curious piece of land wedged between I-76 and the railroad right-of-way, a mostly-forgotten industrial remediation site, is presently under development for an apartment community. The history of this land – an ancient summer fishing ground for the Lenni Lenape – was once known as the village of Pencoyd (pronounced like “Pencode”), site of an rope ferry crossing and the world renowned Pencoyd Iron Works. Considering the present development, there is still time to see some history on the site including a 130+ year old surviving brick structure which the owners claim could be a Furness design. Let’s travel up river and back in time to the year of Penn’s original land grant and subsequent division of this history-rich area.

The Welsh Tract

In November of 1683 the Quaker John Roberts sailed the Morning Star from England to Philadelphia to claim his acreage derived from the famed Welsh Tract, a subdivision sold to a pair of Welsh Quakers directly from William Penn earlier of that year. The Tract – originally thought by the assembled investors to be a contiguous piece of land – was spread about hills west of the Schuylkill from today’s Merion and all about Montgomery, Chester and Delaware counties.

Skull & Heap Map of 1753 showing Lower Merion Township; Roberts Estate at Middle Right | Credit: Free Library of Phila.

John Roberts’ section adjoined that of a fellow ocean traveler, a Miss Gaynor Roberts (no relation; Roberts being a very common name in Wales). Miss Roberts’ father had signed an agreement for land but passed away before disembarking the old country to receive his purchase. Gaynor was destined to be John’s future wife. Was the romance kindled on the Morning Star herself? Coincidence or not, this precipitous coupling netted the future family a total of 180 acres, spreading from today’s City Line Avenue through to Conshohocken State Road along the river. The next spring the Roberts were the first to be married in the new Merion Meeting (the oldest Quaker meeting house in the United States and still extant a few miles up on Montgomery Road), and quickly went about creating a farm, starting a family and building their home. The estate was named Pencoid, meaning “head of the woods” in their native language. The family home was demolished in 1964, making way for today’s Saks Fifth Avenue, Lord & Taylor, Presidential Blvd. and the sprawl of City Line Avenue.

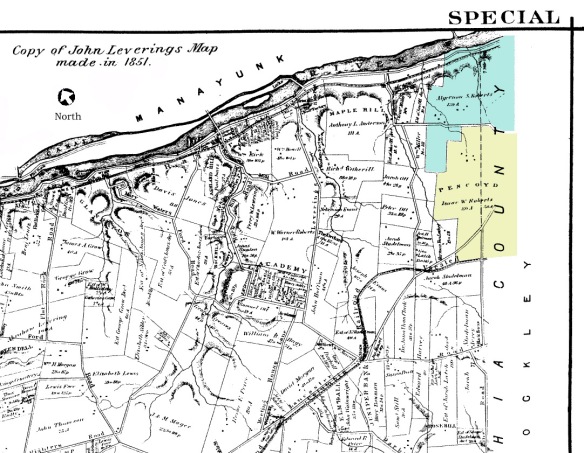

1851 Levering Map Showing Pencoyd and 6th Generation Algernon Robert’s Separate Parcel Just Prior to Establishment of Iron Works | Credit: Free Library of Phila

In summers, the Lenape fished for shad along the Schuylkill shores between the falls near today’s namesake Falls Bridge and up to Flat Rock, a natural crossing near the top of Manayunk. At some point River Road was built along the shore, as the new settlers established shad fisheries in this area throughout the 18th century. At the northern edge of the estate a gentleman by the name of Peter Righter established a rope ferry crossing in 1741; this road and landing was located exactly where the Pencoyd bridge crosses to Manayunk today. For the remainder of the 18th century all would be genteel and quiet in Lower Merion.

Jumping ahead 80 years of bucolic colonial life, fifth generation Isaac Warner Roberts continued farming the land into the early 19th century, supplying dairy and beef to America’s premier metropolis downriver. However industrial and social progress was fast approaching the secluded farmland. The first industrial intrusion was the 1820’s towpath for the Schuylkill Navigation Company.

Anthracite: Pennsylvania’s Gold

In 1808 an East Falls industrialist named Josiah White discovered how to burn anthracite coal, a mineral which lay rich in the upper Schuylkill mountains past Reading. This breakthrough sparked immediate efforts to extract and transport this potentially inexpensive domestic and industrial fuel downriver from Pottsville to Philadelphia and her ports. The Schuylkill Navigation Company, builder of canals for shipping as well as railroads, quickly went about securing property and water rights alongside both shores of the river the 90 miles needed to reach tidewater in the city. Although the Manayunk section of the canal (called a “reach”) extends exactly opposite this site, the navigation also included 46 miles of slack water areas known as “levels”. The Roberts’ side was a level likely used to return boats back upriver when empty and easier to maneuver on natural waters; the label of Tow Path can be seen on the site’s Hexamer survey of 1883 (see below).

1907 View of Philadelphia’s Manayunk Neighborhood with the Pencoyd Iron Works and Laurel Hill West in the Foreground | Credit: LOC

The Navigation thrived for many decades but the railroad proved to be the more efficient method for coal and freight and indeed, the economic engine which fueled 19th century industrial growth. The Philadelphia & Reading Railroad acquired rights all the way up the river and finished the final section of it’s anthracite coal line in 1839. Although not much is known of the nature of the transaction, this right-of-way cut the Roberts’ property from the waterfront as the viaduct ran alongside the Schuylkill on it’s way to the black gold in Pottsville. A double arch provided access from the upper property to the shoreline of the Schuylkill, the road still known today as Righters Ferry Road.

Reading Railroad’s Twin Arch over Righter’s Ferry Road – Original Stonework Dating to the 1830’s. I-76 Visible Immediately Behind | Credit: Mick Ricereto

Cousins in Iron

Isaac Warner Roberts’ 9th son Algernon, not wishing to take over the farm, went to Rensselaer to learn the iron business with the intention of using some of his father’s property for a foundry. Investing $5000 of family money ($144,000 in 2015), he partnered with cousin Percival Roberts on building an iron works on their ancestral river tract. On June 21, 1852 the men hired 4 carpenters, a boy and a few laborers and began construction on their first building. The first hammer forge equipment was purchased from a James Rowland & Co. Their maiden order was placed by the A. Whitney & Sons on October 8 of the same year, for “10 or 20 axles”.

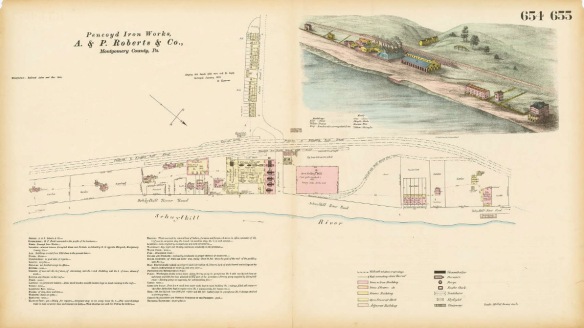

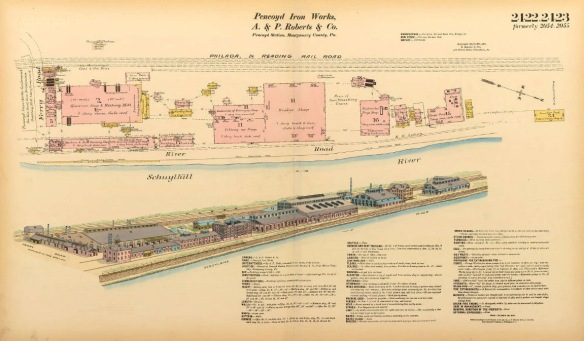

1877 Hexamer Survey of Pencoyd Iron Works; Note the Sylvan Surroundings and Relatively Sparse Building Layout | Credit: Free Library Phila

Entries in the business log describe receiving coal by team (a carriage pulled by horses) and unloading sand from canal boats from the river below. The railroad siding should have provided ideal delivery of raw materials and transportation of finished goods, but curiously the P&R RR would not immediately build the entrepreneurs a railroad siding. As a bicycle ride today would confirm, Righter’s Ferry Road is very steep and back in the days of horse teams, this could not be a preferred entry or exit to the foundry. Luckily the natural endowment of river access would keep business going until the proper rail spur was installed.

Surviving Trio of Worker Houses in Pencoyd Village; Property Attributed to a “Mrs. Sutton” on Author’s 1907 Map

As with many factories, a small community began to grow along the site, naturally called Pencoyd Village. Reports of a rowdy tavern at the north end of the site made for lively news in it’s day. Records for the Continental Hotel describe a large structure near the ferry landing. Small houses for workers were built on Righter’s Ferry Road, with a small row surviving today opposite the lower cemetery gates.

The hills above Pencoyd had been estates owned by several families. In 1869 the property of Anthony Anderson, George Ott and others was purchased to establish West Mount Laurel Cemetery. A Sunday afternoon escape to a sylvan country cemetery was very much a Victorian-era pastime, and with the city’s old Mt. Laurel reaching its capacity, developing a cemetery on the somewhat remote natural and dramatic hilltop siting of West Laurel would have been a solid business venture.

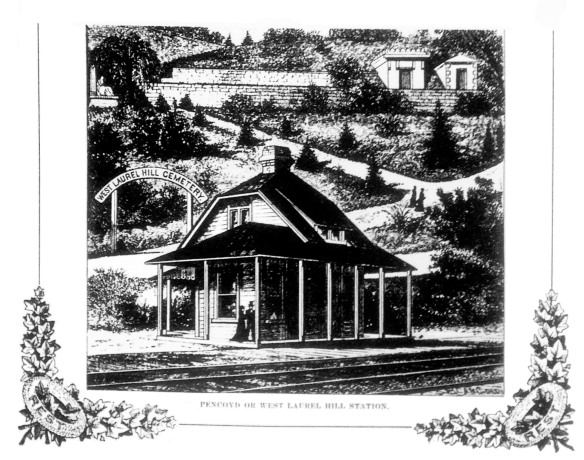

Early maps and the Hexamer Survey point to an original train station (pre-cemetery) on the south side of Righter’s Ferry Road – the same as Mrs. Sutton’s Trio. At some point the train station was rebuilt on the north side of Righter’s Ferry Road, ostensibly to better serve the cemetery visitors. The locations for both stations are covered by the I-76 expressway, with no visible remains to ponder.

Late 19th Century View of Pencoyd Station; Stop Here for Eternal Peace Above, Industrial Chatter Below | Credit: Free Library Phila

The Pencoyd foundry started out with smaller-scale soft wrought iron parts like railroad axles and bridge parts. The firm tentatively moved into structural members, engineering and design, by 1859 the foundry adding “Bridge Company” to it’s name. The firm’s big break came from none other than the giant Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition in 1876.  A very short timeline was given for the design, construction and erection of the buildings; prefabricated iron and glass designs being the natural solution for structures such as Machinery Hall and the Main Building at 21.5 acres floor space, what would then be the largest building in the world. To the surprise of many larger competitors, A & P Roberts Pencoyd Iron Works was awarded this massive contract, even though the mills could not at that time make parts long enough to satisfy the designs. The Hexamer survey shows the diminutive plant around the time of the Exhibition commision, although it should be noted some fabrication work was done off site in Edge Moor.

A very short timeline was given for the design, construction and erection of the buildings; prefabricated iron and glass designs being the natural solution for structures such as Machinery Hall and the Main Building at 21.5 acres floor space, what would then be the largest building in the world. To the surprise of many larger competitors, A & P Roberts Pencoyd Iron Works was awarded this massive contract, even though the mills could not at that time make parts long enough to satisfy the designs. The Hexamer survey shows the diminutive plant around the time of the Exhibition commision, although it should be noted some fabrication work was done off site in Edge Moor.

Expansions and Mergers

1907 Estate Map of Lower Merion Township | Author’s Personal Collection

Throughout the late 19th century Pencoyd would grow exponentially, covering the entire river site with buildings and the addition of rail tracks along the river. The railroad connected a short line across the property to Venice Island with an elegant curving single-track bridge which remains in use today. Around 1900 today’s Pencoyd Bridge was installed to connect with lower Manayunk for additional rail access and as noted by the cemetery’s contemporary marketing, walking traffic from the city to West Mount Laurel. The Hexamer Surveys of 1887 and 1891 show a much more modern factory site.

Hexamer Survey of 1891 – Showing the North Side of Pencoyd Iron Works | Credit: Free Library Phila

Around 1900 the firm merged with the venerable American Bridge Company. Providing truss bridges all around the continent, Pencoyd continued to expand at a prodigious rate. A special highlight for the firm would be the Upper Steel Arch Bridge over Niagara Falls, completed in 1898, at that time the longest steel arch span in the world. Percival Roberts Jr. was chairman during this golden age, his co-founder father vacating this position upon dying early of exhaustion. Mr. Roberts retired on May 24, 1901 after 25 years of service which began shortly after the Centennial. The man was celebrated with a gala on January 18, 1902 at the company’s clubhouse located across the river at Manayunk Ave. and Osborn Street, with all employees in attendance. This property was later donated to the city for the construction of a library, given by the company’s new chairman Andrew Carnegie, who absorbed Pencoyd/American Bridge into his giant United States Steel Co.

Pencoyd c1900 | Credit: LMHS

Consolidation, competition and technological advancements arrived with the new century. Pencoyd was a busy factory through WWI but then began to decline, with the powerhouse steel centers of Pittsburgh and the Rust Belt able to expand their capacities way beyond the little Pencoyd river tract’s 19th century siting could manage. A new rail connection was made at the north side of the site (the existing viaduct showing the date 1917), possibly a connection to the Cynwyd line. Landlocked, the factory steadily declined, finally shutting down the furnaces on December 31, 1943. The I-76 expressway cuts across the top of the property, just above the rail corridor, further isolating this forgotten land. For years the site remained vacant or disused, with recent owner Connelly Containers maintaining some metal industrial buildings and a very busy health club doing business on the southern end of the tract.

The “Furness Building” and Pencoyd Landing

Today, development of the Pencoyd site is well underway. The previously-mentioned apartment complex was quickly erected in the past 12 months, not yet appearing on a Google satellite view. Another set of developers have now begun improving the core area surrounding Righter’s Ferry Road, it’s future apartments, retail and hotel complex to be called Pencoyd Landing. In anticipation of the development the Penn Real Estate Co. renovated a modest brick structure for their offices, the only original A. & P. Roberts structure to survive. This restored building is handsome and the new owners believe the structure could have been designed by Philadelphia’s great architect Frank Furness. The building is described as an office and drawing room with pumping equipment in the 1883 Hexamer survey. Appearing to be integrated in design with the attached machine shop, this would have been a nice commission for Furness. Could it be?

Closeup View of Office and Pump House Building

The new owners have correctly identified Furness-like brick features such as the lovely corbel cornice. Adding curiosity to the case, in 1889 Furness & Evans Inc. designed a house for family member George B. Roberts in Bala Cynwyd (since demolished). Alas, no record exists for this factory and office/pump house building in Furness’ papers. Photographs of the 1889 Roberts house reveal it being very much business partner Evans’ work, more of a standard country home. Evans was likely contracted for the home commission by virtue of relation to the Roberts family through marriage, choosing to run the project through the firm as opposed to solo. Sadly, this otherwise handsome building is likely not a Furness.

Pencoyd Iron Works Office in 2017 | Credit: Mick Ricereto

Visiting Pencoyd Today

Along with this commercial development comes the aforementioned expansion of the Pencoyd Trail, slated to link with the Cynwyd Heritage Trail by way of the hidden 1917 viaduct past the Venice Island bridge at the northern extreme of the property. As seen today, this thickly overgrown strip contains only a few vestiges of the site’s history, including an abandoned rail car and weed-encased tracks deep into the trees. Like your author’s bicycle wanderings, visitors today can catch a glimpse of the abandoned wildness before it disappears completely.

View to Iron Works Site from Atop the Reading RR Viaduct | Credit: Mick Ricereto

The existing metal buildings are not original to the Pencoyd complex and in any rate will be taken down soon. However the steel gantry structure along the water looks to be a relic from the iron works and will be retained in the new design. The original retaining wall under the rail viaduct runs the entire length of the site and is a constant reminder of this place’s rich history. This wall actually formed the interior wall for some factory buildings and cut-off iron bits still protrude from the wall. Paddlers on the Schuylkill can inspect the bridges, ancient granite quay and the crumbling valley stream culverts from the waterline. Although noise from I-76 is very intrusive, biking up to the top of West Mount Laurel gives a lovely view of the entire tract from above.

Rendering of Pencoyd Landing; This Structure Would Replace the Building Above | Credit: JDavis Architects

Before the Pencoyd Bridge reopened, the only vehicular way to the site was by plunging down from City Line between the cemetery roads on Righter’s Ferry. This remains the author’s favorite approach. Catch a glimpse of the secret site of Pencoyd Iron Works before the mystery is gone, and listen close to the old retaining wall for the ghostly sounds of clanging iron and the distant whistle of steam.

Author’s Note: The Hexamer surveys are available to browse on the Free Library’s website, and one can zoom in for some incredibly-detailed high resolution viewing.

Gallery of the Author’s Pencoyd Iron Works Site Photos in Early 2017: